Bikes are memory makers. They pinpoint life with feel-good moments. Think of that easy-flowing, dreamlike descent, your proudest race time, or the adventure you survived and the bike that carried you through it. At the heart of that adventure are your bike’s components.

In mountain bike development, each step brings a raft of new possibilities, letting us ride longer and further, with much more fun and banking more memories along the way.

When Shimano ambassador Dan Milner recently rummaged through his box of old and near-forgotten spares stored at the back of his workshop, he emerged with a handful of dusty retro components. We asked Dan to walk us through the place of each component within the giant leaps and bounds of his MTB career, spanning more than 35 years.

The Shifter: 1986 Shimano XT M732 3x7-speed vs. 2022 XT M8100 1x12-speed

Taking today’s smooth and perfectly indexed shifting systems for granted may be easy. But when Shimano introduced SIS – Shimano Index Shifting – the MTB world was forever changed. In 1986, SIS was widely accepted in road biking, but its reception within the mud-clogged off-road world was lukewarm.

Replacing the inaccuracies of friction shifting, the indexed XT – with the above-bar thumb-shifter – introduced reliable and accurate one-push gear changes, which came in handy as I started racing cross-country laps around muddy farmers’ fields in southern England.

XT’s sophisticated, stealth black finish placed it head and shoulders above its grey sibling Deore in terms of desirability, and the 3x7 shifting combination gave me all the gears I could ever want, until the XT 8-speed system came out eight years later.

Fun fact: the 1986 catalog warned that “SIS may not function properly if used with frames that route the shift cable inside the frame tubes.”

The Derailleur: 1998 Shimano XTR M951 8-speed vs. 2022 XT M8100 12-speed

In 1991, the “R” in XTR meant Shimano elevated the hardwearing XT series to an ultra-worthy race standard that had me brimming with excitement. This was an era when we were quick to shed every surplus gram from our XC bikes. Available in a ‘medium cage’ – i.e., quite short – version, the tiny, compact XTR derailleur boasted the snappy race shifting we needed but only found by fitting Dura Ace short-caged derailleurs to our mountain bikes. Of course, today’s cassette tooth profiling and finely engineered derailleurs take care of this despite their enormously ‘long’ cages.

In 1998, Shimano added a gear cable roller guide to the rear of the derailleur in a short-lived show of technical performance that got us riders very excited – but proved unnecessary, as it added weight and the shifting worked fine without it.

Of course, with cassettes' gear capacities ranging from 12 to 32 teeth, even XTR relied on triple chainrings up front for the wide gear range we needed, something today’s 1x12 set-up delivers with ease.

The Frame: 1990 Cannondale SM800 vs. 2023 Yeti SB140

Components mean little without a skeleton to hang them on, and while the seamless welds of my aluminum 1990 Cannondale M800 are mirrored by the smooth carbon layup of my current Yeti SB140, that’s about as far as their similarities go. Over the three decades that have brought me from the Cannondale to the Yeti, much has changed in the demands we put on our bikes — and how component development has reacted to those demands. A frame is, in fact, the ultimate showcase for the technology of its time.

Case in point: 180mm disc brake caliper mounts have replaced cantilever brake bosses. Headtubes have swollen in diameter, tapered and slackened by 6 degrees (the Cannondale sports a 71-degree head angle), and seat tubes now swallow fat-tube dropper posts instead of slim 27.2mm rigid posts. Meanwhile, today’s rear triangles welcome 27.5” and 29” wheels with 2.6” tires instead of the 26”-1.9” tires that were my racing choice in 1990. Also, the rear dropout spacing has widened from 135mm to 148mm, accommodating wider hubs for better wheel strength without compromising on the chainline.

Ultimately, though, a mountain bike is only as strong as its rider. While today’s empowering frame geometry, drivetrains, and brakes keep me out there longer, my old steep-angled XC Cannondale saw me through a lot of fun times, albeit along with plenty of over-the-bars moments!

Fun fact: the wheelbase on the CannondaleM800 was a whopping 162mm shorter than the Yeti SB140’s.

The Brake: 1990 Shimano LX vs. 2021 Shimano XT M8120 hydraulic

A world apart from the power of the 180mm rotors and 4-piston XT brakes I run now, the 1992 LX cantilevers proved a simple and robust solution for my 10-month-long bikepacking trip around South America. Pulled by a central cable, there was an art to balancing these stubby cantilever brakes so they simultaneously touched the rim.

Although superseded by the much more powerful V-brake, these cantilevers had the potential for strong braking – if you had the right lever. When the 1998 Shimano LX lever arrived, it punched well above its weight in performance and innovation, despite being a tier down from XT in the lineup. These short two-finger levers were a revelation, letting us ditch the previous three-finger monsters and offering adjustability.

Three-position modulation (H-M-L) settings let me customize the amount of throw on the lever required to engage the brakes (useful at a time when so many different cantilever designs were on the market), and they also added ‘Servowave’, that alters the pull on the brake pads the more the lever is engaged, which leads to finer braking control.

Fun fact: Servowave works so well that it is still used throughout today’s Shimano brake lever lineup, including the current M8100 XT disc brakes.

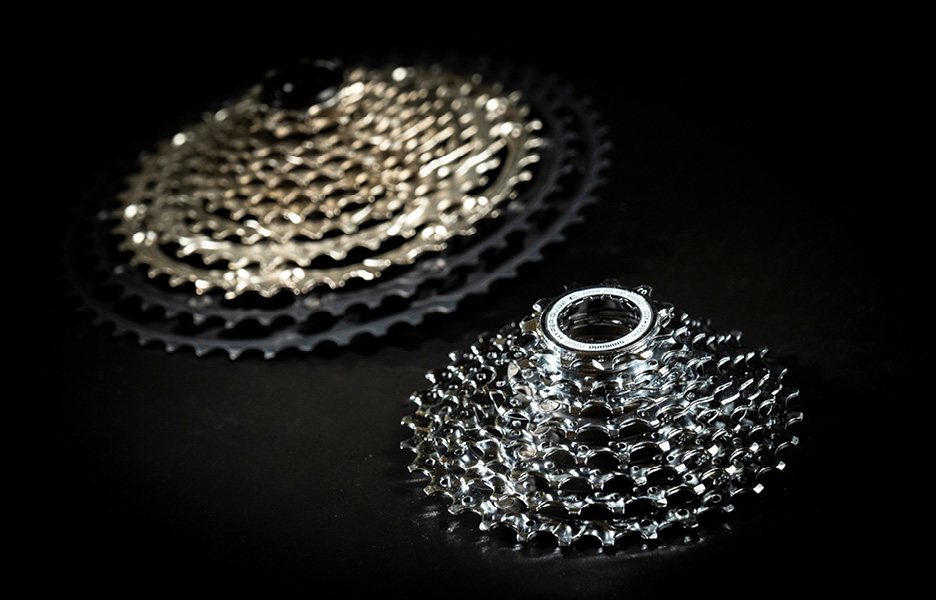

The Cassette: 1994 Shimano XT 8-speed vs. 2022 XT 12-speed

Having sweated up hillsides armed with 18 at first, followed by 21 gears for nearly a decade, I had to wait until 1994 to get the full 24 gears offered by Shimano’s eight-speed cassette.

Tiny as it looks now next to the behemoth that is the current 51-tooth incarnation, the Hyperglide 8-speed XT cassette quickly became my best friend. Compared to the preceding 7-speed gearing, it delivered smoother, closer shifts for uninterrupted cadence while adding two additional teeth to the largest sprocket to deliver a knee-saving, hill-beating 30-tooth low gear. Meanwhile, the smallest sprocket dropped from 12 to 11 teeth, crucial for keeping the torque on longer during descents. Yes, this shiny, compact masterpiece was everything its glinting, chrome finish suggested, and more!

Slotting onto a separate Hyperglide freehub body made swapping or replacing cassettes a quick, simple job. Especially compared to trying to remove stubbornly seized freewheels of old — a technology I welcomed just as much when working as a bike shop mechanic in the early 1990s as I do now with the current 12-speed micro spline freehubs.

The Chainset: 1997 Syncros triple vs. 2022 Shimano XT 1x12

As a fan of climbing up big, steep hills, the most significant evolutions in mountain biking (after suspension) are gear range and the increased effectivity of the single chainring set-up for delivering this wide range of gears.

Replacing triple and double rings with a single chainring became a game changer. Especially when you combined this with 51-tooth cassettes to boast the same huge gear range we once found on awkward 3x8 set ups, without the hassle and chain abuse that came with front derailleurs.

Single chainrings are the most noticeable development, but there is so much more to crankset evolution. Back in 1997, the ‘state of the art’ bespoke crankset boasted a raft of what were actually quite awkward features — the sort of things that were fine then but you wouldn’t want to return to now: Square taper bottom bracket interfaces that persistently came loose. Slim, lightweight crank arms that flexed. And chainrings attached by fiddly little chainring bolts that were easily lost under the work bench among dust and grimy, empty crisp packets.

Each of these components served me well in their time, leading me into new chapters of my mountain biking career – and serving up new memory moments. When I look at these old components, it’s clear that even prophetic vision wouldn’t suffice to tell us where mountain biking would be just two or three decades later, and how those components would evolve. I’m glad to have been a part of it, and it makes me even happier to be where we are now.